Pierre Akkelian – Entrepreneur & Philanthropist

By Lalai Manjikian

The short version of the Akkelian story was featured by 100 Lives. Հայերեն Բիէր (ՊԻԵՌ) Աքքէլեան

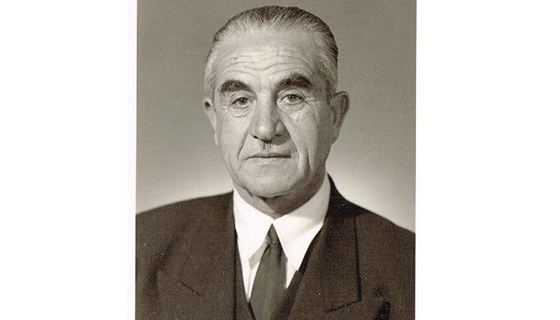

Born in Aleppo, Syria, and raised in Montreal, Canadian-Armenian entrepreneur and jewelry business executive Pierre Akkelian is on a mission of global proportions. He is committed to raising awareness of the heritage of Armenian jewelry and to transmitting this knowledge to future generations of jewelers. Pierre believes that “Armenians are to jewelry what the Swiss are to watches.”

The grandson of Armenian genocide survivors, Akkelian has taken what was once a small family business and turned it into a nationally acclaimed company that reaches a global market. Today, Canadian Gem is known as Canada’s largest pearl distributor and has earned the reputation of being, as the company’s tagline states, “Canada’s most trusted pearl specialists.”

On his long journey toward success, Akkelian has remained devoted to his Armenian roots. Besides being passionate about Armenian artisanship and culture, he also is an advocate for genocide studies and awareness, namely through his involvement with the Zoryan Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies.

Akkelian attributes his success in both business and philanthropy in large part to being Armenian.

Akkelian’s family suffered tremendous losses during the Armenian genocide. Today, while he recognizes the traumatizing effects of genocide on survivors and even on their descendants, he also sees a correlation between his accomplishments and the loss suffered by his family. “It becomes part of your genetics, the survival and the perseverance are part of your DNA,” he says.

Waking up to Genocide

All four of Akkelian’s grandparents were genocide survivors. In 1965 at the age of 11, he attended the 50th anniversary of the Armenian genocide held at the Forty Martyrs Cathedral in Aleppo. He thus recalls the importance of the commemorative events taking place in Syria, where countless Armenians had found refuge: “There was a huge movement. All of a sudden, Armenians woke up after 50 years.” He recounts how the cathedral was draped in black, an image that has clearly marked Akkelian. “It was very sad and it was the first time in my life that I felt the effect of genocide on our people.” After attending the commemoration, Akkelian took a deeper interest in the genocide and began probing his paternal grandmother, Khatoun nene, who was a survivor from Urfa (modern-day Sanliurfa in southeastern Turkey).

Khatoun lost both of her parents and many relatives when Turks burned down Urfa’s majestic cathedral where 3000 community members had taken refuge during the Hamidian massacres in 1895 Khatoun was particularly traumatized by her aunt committing suicide with her newborn baby to avoid burning by the raging fire, by throwing herself down from the cathedral’s bell tower. Akkelian recounts how Khatoun identified her father Kaspar’s face-covered corpse, laying in their ancestral home courtyard, based on the unique hand knit socks he had on. Furthermore, her mother’s bloody handprints on their home courtyard wall attested to her struggle as she was strangled with the thick gold necklace she wore.

After a decade or so in an orphanage in Urfa, Khatoun married her first husband Garabed Voskerichian, an engineer in charge of design at a German carpet weaving company in Urfa. By 1915, they had four children. When the mass deportations and killings began, gendarmes took Garabed away. At the time, Garabed was in hiding. He agreed to come out only because the German manager of the carpet factory where Garabed worked accompanied the gendarmes. They assured Khatoun and others that Garabed would be safe, saying “Don’t worry sister, we will bring him back.” It was the last time Khatoun saw her beloved husband who was a cultured man “piano playing aristocrat” –Khatoun also lost all four of her children from this marriage during the genocide. Although she did remarry and start a new family later on, Khatoun asked to be buried with the picture of her first husband.

Khatoun Kasparian Voskerichian Akkelian. Photo: Vartan Derounian

Khatoun did not openly speak of what had occurred to her and to her immediate family during the genocide in great detail. Akkelian recalls that his mother and father instigated Khatoun to talk about the past. It was common for survivors to think that upsetting secrets from the past were best to be forgotten and not brought up. When asked how her children died, she told them that her newborn died due to a lack of milk and that she placed the baby in the cart collecting the dead. The circumstances surrounding “the death” or possible abduction of her eldest child are not known, but sexual violence was most likely one of the culprits. As for her other children, she would simply cry and not elaborate much. At least two of Khatoun’s children were likely abducted, leading Akkelian to speculate that he could well have blood relatives in Turkey today.

After enduring these losses, in 1915, Khatoun took up an offer from a rich Turk agha who was fleeing Van, to join his caravan leaving Urfa and heading towards Aleppo. Khatoun joined the caravan hoping to be reunited with her half-brothers Kasparians (previously Demirjians) who lived in Aleppo. During the journey, the agha from Van wanted Khatoun’s hand in marriage, as she was known to be a beautiful woman. In the meantime, she was taken to the agha’s harem in Aleppo, guarded by an eunuch. There, the other wives and women saw her beauty as a threat and planned her escape. The eunuch notified Khatoun’s brothers that Khatoun was in Aleppo and informed them of where she was staying. Her brothers were able to help Khatoun escape, as part of a clandestine operation organized by the agha’s women with the help of the eunuch. However the agha from Van found the brothers who had a successful Blacksmith business next to their home and kept asking for Khatoun to be returned to him as his wife and demanded to know what happened to her. In order for him to stop pursuing Khatoun, the brothers eventually told the agha that their sister had died of shingles.

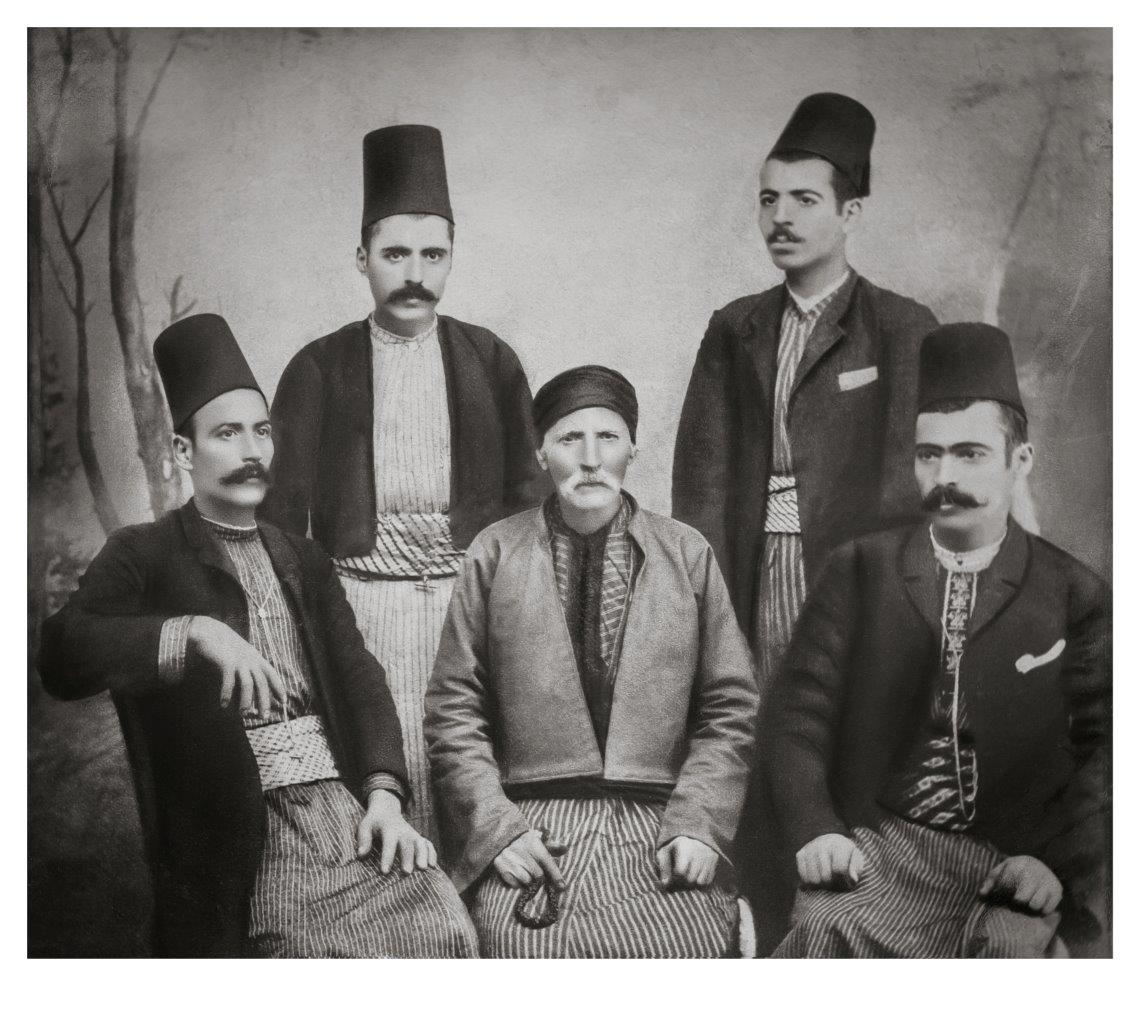

A close shave: Bedros Akkelian and Djemal Pasha

Akkelian’s paternal grandfather Bedros Akkelian had moved from Urfa to Aleppo prior to the genocide (between 1913-1914). Bedros was a renowned homeopath with a great following. A newly opened German hospital in Urfa offered him a clinic in their building to attract patients. Bedros treated a number of famous patients, saving them from catastrophic medical conditions, including Vartan Derounian who was the most renowned photographer in Aleppo at the time. In fact, Akkelian’s grandmother Khatoun’s and grandfather Bedros’ family pictures were taken by Derounian. Doctors had planned to amputate Derounian’s right hand following an accident. However, Bedros treated Derounian’s hand through homeopathic healing, and the photos he took are in appreciation for saving his hand. Derounian also gifted Bedros a carpet, which the family unfortunately no longer possesses. However the Akkelian family does own one of the rare carpets woven by orphans of the Armenian genocide. Bedros had purchased this carpet from the owner of the workshop were the orphans worked. Pierre Akkelian’s father, who was born in 1920, grew up playing on that unique carpet.

In Aleppo, Bedros Akkelian also worked as a barber for an American-Armenian who had moved back from America and owned a modern barbershop at the time.

One of Bedros Akkelian’s regular customers happened to be Cemal Bey and later Djemal Pasha, the prominent Ottoman military leader. Djemal Pasha trusted Bedros to shave him on a daily basis, bringing knives in close proximity to his neck. Because Bedros had earned the Pasha’s trust, other Turkish military leaders would go to him for a shave as well. This scenario is paradoxical, considering the fact that Ottoman authorities killed Bedros Akkelian’s first wife and their four children in 1915.

“We cannot understand how they are allowing an Armenian to shave them, while they are carrying out massacres on Armenians,” explains Akkelian in reference to his grandfather’s clientele. However, Akkelian points out that there are some historical accounts that suggest how the power struggles between three Young Turk leaders with absolute control over the Ottoman Empire, interior minister Grand Vezir Talat Pasha and war minister Enver Pasha, lead naval minister Djemal Pasha to have his own plan. Djemal, who was of Cherkess origin, intended on keeping and protecting Armenians in Aleppo instead of deporting them all to Der ez-Zor, in order to potentially exploit Armenians for the country’s development, if he ever became the new Sultan of Turkey.

Following an accident where Bedros cut his finger at the American-Armenian barbershop, the owner paid Bedros only half his salary for that month, on the pretext that he was working with only one hand. This prompted Bedros to leave the shop, refusing that particular payment arrangement. Two gendarmes, sent on behalf of Djemal Pasha, set out to see why Bedros no longer worked at the barbershop, as Bedros was the barber trusted by Turkish leaders. Once Bedros told Djemal Pasha what had occurred with his previous employer, the military leader proposed that Bedros choose any shop he wanted in Aleppo, with the intention to confiscate the space for the war effort and turn it into a new store. Bedros did not wish to ruin anyone’s business and instead suggested that he set up shop in a big store at a location next to where the caravans would arrive in Aleppo. The original shopkeeper there sold coffee and made fezes. Bedros proposed to the shop owner that they split the store and that they share customers. That is how the Akkelian barbershop came into existence in Aleppo, catering to many local dignitaries and Turkish military members.

In 1916 Bedros Akkelian married Khatoun. Ironically, Bedros has once asked her hand in marriage way back in Urfa when she was still in the orphanage, an offer that was rejected. Bedros became a prominent community leader. He was involved in the local church-diocese committee and also became its treasurer. They had six children together: Araxie, Anahid, Kegham, Papken, Karnig and Angel. Both Kegham and Papken died in their infancy.

Hearing these disturbing accounts about his grandmother’s life had such a profound impact on Pierre that at the age of 11, he decided to rebel and turned into an atheist, a point of view he holds until this day.

Another incident involving Bedros and Djemal Pasha revolves around a man by the name of Arshavir Yessayan. Akkelian states that this incident well known by family members is in fact recorded in historical accounts and archives unearthed by scholars.

Yessayan appeared to be a menace and would go around the community in Aleppo blackmailing individuals. Those who did not pay up would face exile. Some Armenian community leaders in Aleppo approached Bedros Akkelian asking him to intervene, given the fact that he personally knew Djemal Pasha. Bedros was reluctant to get involved at first; however after hearing testimonials from family members of those who had been threatened, jailed and exiled by Yessayan, Bedros finally decided to approach Djemal Pasha about the issue. At first, the military leader cautioned Bedros advising him to not get entangled in case these occurrences were not founded. However, when Bedros informed Djemal of the family accounts he had heard, confirming that these stories were true, the military leader decided to bring Yessayan to court. After the judge read the accusations in court, Yessayan pleaded not guilty and proceeded to claim, “you have no right to judge me.” He then immediately produced a document from his pocket stating that he is the personal agent of Talaat Pasha – which led to the case being dropped. Arshavir was escorted away from Aleppo under protection and later in 1918 beaten to death by Armenians in Adana.

It is also noteworthy that when Kemal Attaturk was in Aleppo, Bedros Akkelian served him. In 1918, after the First World War, Attaturk asked Bedros Akkelian to come back to Turkey with him, given that he had great trust in him and that they maintained a personal and amicable relationship. However, Bedros respectfully declined. Bedros later advised his son Karnig “to get as far as possible from places with mosques once he amassed enough fortune.” This might one of the primary reason why Akkelians ended up in Canada in 1970.

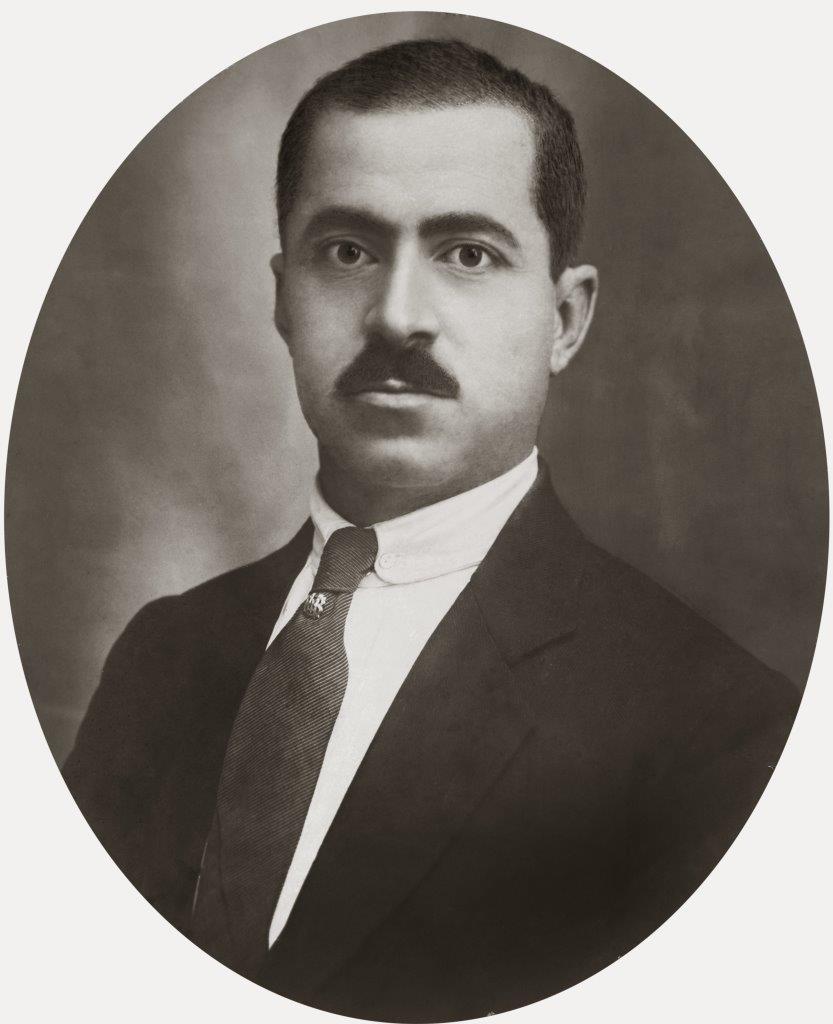

Akkelian’s maternal grandfather, Stephan Megerdichian from the Cilician town of Yarpouz (near Adana, south of modern-day Turkey), owed his life to his employers: company owner Edward Salem, an Arabic speaking man with Greek Orthodox roots, and to company managers Khawaja Elias Certain (who always rode his white Arabian horse) and Khawaja Abbdo Gharelias (known for riding his red Arabian horse). He was saved near Maskanah, the town where he worked at a company that shipped licorice root used for medicinal purposes amongst others to United States, as secretary and bookkeeper, thanks to his proficient language and accounting skills. His mother and siblings stayed with him, while other family members perished on a death march to Der ez-Zor in the Syrian deserts.

Megerdichian eventually became one of the founders of the Armenian community in Raqqa, northern Syria, where a church and a school were established. He ensured that the school maintained a good reputation and provided a quality education despite limited resources. He and his wife also owned two successful businesses in Raqqa. When Akkelian’s mother complained to her father saying that you are focusing too much of your energies in the Armenian community rather than the business, Megerdichian replied: “Don’t you think we lost enough as a nation? Do you want to lose more, that there be no [Armenian] school, no Armenian [language] being taught? Isn’t it enough that we lost 1.5 million?” She no longer probed him.

Akkelian’s maternal grandmother Katerisa Mekenissian was from Kayseri. Her father, Garabed Mekenissian, a mechanical engineer by profession, moved around the Ottoman Empire installing industrial machinery. When Katerisa’s father felt that the situation was about to deteriorate, he decided to place Katerisa at the Shalom Centre, a school for women run by German nuns in Marash.

Garabed Mekenissian had seven sons, all of whom perished during the Genocide. One of them was hanged in Marash on a number of falsified charges – one of the twenty Hunchakian martyrs executed by gallows on June 2, 1915. After all his family members were massacred with the exception of Katerisa, Garabed joined General Antranik’s Armenian volunteers fighting against Ottoman army as an artillery expert.

One hundred years later

On April 24, 2015, Pierre brought five roses to Tsitsernakaberd, the Genocide memorial in Armenia’s capital Yerevan – one in memory of each grandparent and a symbolic fifth for the entire 1.5 million individuals who perished. “The pain comes back, somehow. On the other hand, as a nation we are able to survive and prosper after such trauma,” he recounts.

Akkelian himself is living testimony to survival and prosperity. Besides being president of Canadian GEM, he is also a co-founder with his brother Papken of Nishi Pearls, Hong Kong. Over the past three decades, Akkelian has significantly contributed to shaping the Canadian jewelry industry, particularly through his involvement with the Canadian Jewellers Association (CJA). His vigorous efforts were recognized when the CJA presented Akkelian with the 2015 Chairman’s Award. CJA chairperson Tanya Parrish presented the award on behalf of the Canadian jewelry industry for his contribution to the improvement of the Canadian jewelry industry “by conscientiously maintaining the highest professional standards” throughout his career. According to her “Pierre has been a tireless supporter of the industry, its associations and its cultural and charitable efforts. He has championed international and national causes for the industry and improved the standing of the industry with governments, media, associations and individuals over the years.”

Throughout his career as jewelry business executive, Akkelian has served on countless intergovernmental and industry committees on both international and national levels.

He has played an important role in shaping the diamond industry in Canada by advocating for the establishment of a “Canadian standard” for diamonds. During a speech he delivered in 1999 at a conference in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, he suggested an agenda for creating a value-added diamond industry in Canada. This agenda entailed setting Canadian standards for diamonds, branding them with a patented logo, and allowing Canadian diamonds to be cut by top experts regardless of the country, in order to attain “Canadian standards of excellence in a borderless world” Furthermore, once diamonds are cut and authenticated to Canadian standards, the international recognition of Canadian diamonds would prompt major multinational processing centers to establish themselves in Canada.

In 2011, Akkelian delivered another speech in Gaborone, Botswana, South Africa at a conference organized by the World Bank entitled “Diamond Processing Exchange.” He represented Armenia at this conference and spoke about the importance of international networking and the support of the diaspora in the diamond industry in Armenia. According to Akkelian, these contacts were “instrumental in transferring knowledge and skills and supplying rough diamonds in post-communist days until an indigenous industry was formed and supply channels re-established with Russia.” He urged attendees to make the best use of their networks and knowledge resources to create an African diamond brand to capitalize on the sympathy and support (for homegrown industry that creates jobs) most westerns have for Africans.

One of Akkelian’s main achievements within the Canadian jewelry industry remains his pivotal role in abolishing the 88-year-old Canadian Excise Tax on jewelry in May 2006. As CJA board member and President 1996-97, he lobbied the Canadian federal government on behalf of the jewelry industry and dealt with the top echelon of Canadian government including Prime Ministers, ministers, senators and bureaucrats. “It was a complicated file,” Akkelian remembers. “With the Armenian gene, the DNA, you don’t give up. One hundred years have passed, the Turks have still not accepted the Genocide, and we are still fighting. So, the Canadians are thinking that I’m going to give up easily. No way, we found cracks; we passed the bill to eliminate the excise tax through the three readings in the House of Commons, then the Senate. It was impossible and unprecedented; no private member’s bill has ever eliminated a tax against the wishes of Minister of Finance, but we did it.”

Akkelian later used his government contacts to lobby for Armenian causes. In fact, Akkelian was one of the founding members of the Congress for Canadian Armenians (CCA) in 2006 and the chairman for the CCA’s National Committee in charge of lobbying. In April 2009, on the 5th anniversary of the Canadian Parliament passing a resolution that recognized the Armenian genocide, Akkelian organized a reception on Parliament Hill on behalf of CCA member organizations. During the reception, members of Parliament, opposition leaders and then Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, who had voted in favour of the Armenian Genocide bill, were recognized with certificates on behalf of the community, applauding their humanitarian stance. This event, as well as the official letter CCA received from the Prime Minister recognizing the Armenian genocide, angered the Turkish government. As a result, they called back their ambassador “for consultation.”

Akkelian has made another important contribution within the realm of the Armenian cause in Canada. Through his connections with the Montreal Gazette’s publisher Michael Goldbloom, he played a vital role in changing the Gazette’s policy when writing about the Armenian genocide. Through Akkelian’s efforts, the Gazette eliminated the term “alleged” when referring to the Armenian Genocide, as well as the insistence of presenting the Turkish denialist rhetoric every time the word genocide was used. Akkelian rallied various leaders representing political, religious, cultural, and business factions of the Armenian community in Montreal, including members from the Ramgavar, Tashnag, AGBU, CABC, the Armenian Diocese and Prelacy. After meeting at Akkelian’s office and agreeing on a strategy, they were able to present a unified and multifaceted front to the Gazette editorial board. Following that meeting, the Gazette modified their policy.

Furthermore, Akkelian played an instrumental role in putting together a legal team to defend Turk academic Taner Akcam against Turkey in the European Court in Strasbourg. Human rights lawyer Payam Akhavan, supported by Harry Dikranian, Vrouyr Moughalian and Sheila Paylan successfully defended Akcam and the court ruled against the Turkish government’s law 301, that the Turkish government used to prosecute anyone who “insulted” Turkishness by using the word “genocide” in Turkey.

Since the year 2000, Akkelian has a been staunch supporter of the Zoryan Institute. Along with Diran Avedian, he put together the “Zoryan Dream Team” and organized a number of presentations delivered by researchers and academics in the field, such as Yair Auron, Taner Akcam, Hilmar Kaiser and others.

Alongside his efforts to bolster the jewelry industry and lobbying for Armenian causes in Canada, Akkelian holds his other missions to heart. In 1997, he founded the Armenian Jewellers Association (AJA), an association that creates links among Armenian jewelers worldwide — a strategy Pierre has implemented successfully to advance his business. In 2011, Akkelian became co-founder of the Armenian Jewellers Foundation (AJF) with the aim to document and advance Armenian and world jewelry heritage and establish educational programs for young emerging designers and gemologists.

As chairman of the AJF, Akkelian was involved in organizing an unprecedented exposition to commemorate the centennial of the Armenian Genocide in St. Petersburg, Russia. The exhibit displayed Armenian artifacts rescued by Alexander Miller and a small team of Russian ethnographers from Western Armenia during the Genocide, including costumes, jewelry, and carpets from the city of Van, the towns of Alur, Bitlis, Moks, Mush, Shatakh, and neighboring villages. The Foundation funded and managed the project, which officially opened on April 27 at the Russian Museum of Ethnography. A catalogue entitled “Treasures of Western Armenia,” which encompasses the photographs of the artifacts, was published in conjunction with the exhibit.

Full circle

Pierre Akkelian is also the driving force behind another initiative that was launched by the Armenian Jewellers Foundation and supported by Hay Doun, a Montreal-based NGO, that has resettled over 900 Syrian-Armenians in the city during 2015. Akkelian has set up an educational grant program aimed to provide newly resettled Syrian-Armenian refugees an opportunity to enhance their gemological skills and knowledge surrounding gemstones. On September 9, 2015, a group of 11 Syrian-Armenians began their studies at the Montreal Gemological School, one of the reputed jewelry sector academies in North America.

Akkelian’s own family members were once refugees in Aleppo, Syria. Today, he is ensuring that Syrian-Armenian refugees are given an opportunity to start their new journey in Canada. With this particular initiative, Akkelian’s contributions to the community have come full circle.

Akkelian is married to professional artist Norma Papazian. Together they have three children: Arka runs the Hong Kong bureau of Nishi Pearls and is in charge of the company’s technological component. Bedros, also known as Spidey, is an internationally renowned hypnotist, mentalist, who has made countless television appearances and has a long list of live performances. Lastly, Alique, is creative director of Nishi Pearls.

Pierre’s interviews & reports – English

- Etchmiadzin visit with Matt Stuller The founder and Chairman of Stuller Inc. the largest jewellery manufacturing and distribution company in North America.

- Maria Titizian’s Civilnet interview about the Treasures of Western Armenia was recorded during my visit to Yerevan on April 23, 2015 to attend 100th anniversary of the genocide.

- The founding of (AJA) Armenian Jewellers Association Maria Titizian’s interview or read the AJA Genesis report.

- “Armenians in 2115, participant in the 2014 Gulbenkian Foundation strategic seminar in Lisbon to identify challenges faced by Armenia and Armenians in the coming decades up to 100 years from now!

Video & interviews – Armenian